From 1930-1945, the world saw a great deal of suffering and conflict. The Great Depression, which began with the Wall Street crash in October 1929, and the Dust Bowl, only ended with a ramp up to production as we entered World War II following the Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941. The years of struggle, poverty and unemployment, followed by the war effort, rationing and the draft, FDR’s Executive Order 9066 forcing Japanese Americans into incarceration, and the decision to end the conflict in the Pacific with the atomic bomb: upheaval, fear, uncertainty were ever present in these years. Some of that is well reflected in books written and published.

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett, 1930

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett, 1930

After a series of unsatisfying jobs, Dashiell Hammett became an agent for Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency in 1915. Hammett enjoyed the thrill of the sometimes dangerous job and worked, as his health permitted, on and off as a Pinkerton detective for the next seven years. When poor health forced him to end his employment at Pinkerton’s, Hammett began writing detective stories, using his real-life experience as source material. After becoming a leading contributor to the popular magazines of the period, Hammett turned his attention to writing novels. His third novel, The Maltese Falcon, remains to this day one of the most widely recognized and respected works of detective fiction. Readers who have never picked up The Maltese Falcon nor viewed the classic 1941 film adaptation, which follows the novel practically word-for-word, might feel a strong sense of familiarity when they first encounter the story. In this book, Hammett invented the hardboiled private eye genre, introducing many of the elements that readers have come to expect from detective stories: the mysterious, alluring woman whose love may be a trap; the search for an exotic icon that people are willing to kill for; the detective who plays on both sides of the law to find the truth, but who ultimately is driven by a strong moral code; and enough gunplay and beatings to make readers share the detective’s sense of danger. Throughout the decades, countless writers have copied Hammett’s themes and motifs, seldom able to come anywhere near his near-perfect blend of cynicism and excitement.

![The Black Echo [Paperback] michael-connelly](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81oMZ4D7bXL._AC_UY218_.jpg) Read Along: The Harry Bosch series by Michael Connelly (beginning in 1992), which starts with The Black Echo. Connelly started out as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times covering the crime beat. His knowledge of the inner workings of LAPD and crime investigations inform this detective series. The Los Angeles setting for all of his books is nearly a character in itself, so fully fleshed and ultra-detailed, down to one of Harry Bosch’s regular haunts and his favorite meal there (fried pork chops with salt, which were in real life exactly as Connelly writes them into his fiction–at least until 2022, when the presumable economic hardships and changes of the Covid-19 pandemic shut the doors of Chinese Friends restaurant after 50 years in business. Connelly writes with an eye for telling detail and an ear for snappy but natural dialogue, and his books are “modern noir” works along the Hammett continuum . Harry Bosch a detective who goes by the dictates of his own unbreakable moral compass, and with some dark corners in his past that make the series compelling and poignant.

Read Along: The Harry Bosch series by Michael Connelly (beginning in 1992), which starts with The Black Echo. Connelly started out as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times covering the crime beat. His knowledge of the inner workings of LAPD and crime investigations inform this detective series. The Los Angeles setting for all of his books is nearly a character in itself, so fully fleshed and ultra-detailed, down to one of Harry Bosch’s regular haunts and his favorite meal there (fried pork chops with salt, which were in real life exactly as Connelly writes them into his fiction–at least until 2022, when the presumable economic hardships and changes of the Covid-19 pandemic shut the doors of Chinese Friends restaurant after 50 years in business. Connelly writes with an eye for telling detail and an ear for snappy but natural dialogue, and his books are “modern noir” works along the Hammett continuum . Harry Bosch a detective who goes by the dictates of his own unbreakable moral compass, and with some dark corners in his past that make the series compelling and poignant.

The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, 1931

The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, 1931

Pearl Buck was one of the most widely read American novelists of the twentieth century. When she published her most popular and critically acclaimed novel, The Good Earth, in 1931, she was living in China as the wife of a Christian missionary. By that time, she had lived in China for about forty years and brought to her portrayal of Chinese rural life a knowledge that few if any Western writers have possessed. The novel is about a poor farmer named Wang Lung who rises from humble origins to become a rich landowner with a large family. Although Wang Lung is a fundamentally decent man, as he becomes wealthy and acquires a large townhouse he becomes arrogant and loses his moral bearings, but he manages to right himself by returning to the land, which always nourishes his spirit. The Good Earth contains a wealth of detail about daily life in rural China at the end of the nineteenth century and in the first quarter of the twentieth century; it shows what people ate, what clothes they wore, how they worked, what gods they worshiped, and what their marriage and family customs were. The novel is written in a simple but elevated, almost Biblical style, which lends dignity to the characters and events. It was widely praised for presenting American readers with an accurate picture of a country about which they knew very little in the 1930s.

Read Along: Wuhan by John Fletcher (2021)

Weaving together a multitude of narratives, Wuhan is a historical fiction epic that pulls no punches: the heart-in-mouth tale of a peasant family forced onto a thousand-mile refugee death-march; the story of Lao She – China’s greatest writer – leaving his family in a war zone to assist with the propaganda effort in Wuhan; the hellish battlefields of the Sino-Japanese war; the approaching global conflict seen through a host of colourful characters – from Chiang Kai-Shek, China’s nationalist leader, to Peter Fleming, a British journalist based in Wuhan and the prototype for his younger brother Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, 1932

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, 1932

Aldous Huxley’s most enduring and prophetic work, Brave New World, describes a future world in the year 2495, a society combining intensified aspects of industrial communism and capitalism into a horrifying new world order. Huxley’s title, taken from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, is therefore ironic: This fictional dystopia is neither brave nor new. Instead, it is so controlled and safe that there is neither need nor opportunity for bravery. As for being “new,” its unrelenting drives toward management and development, and its obsessions with predictable order and consumption, are as old as the Industrial Revolution. Coupling horror with irony, Brave New World, a masterpiece of modern fiction, is a stinging critique of twentieth-century industrial society.

Read Along: The Year 200 by Agustín de Rojas (2016)

Read Along: The Year 200 by Agustín de Rojas (2016)

Centuries have passed since the Communist Federation defeated the capitalist Empire, but humanity is still divided. A vast artificial-intelligence network, a psychiatric bureaucracy, and a tiny egalitarian council oversee civil affairs and quash “abnormal” attitudes such as romantic love. Disillusioned civilians renounce the new society and either forego technology to live as “primitives” or enhance their brains with cybernetic implants to become “cybos.” When the Empire returns and takes over the minds of unsuspecting citizens in a scenario that terrifyingly recalls Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the world’s fate falls into the hands of two brave women. Drawing as much from the realms of the adventure novel, spy thriller, and political satire as from hard science fiction, horror, and fantasy, The Year 200 has been proven prophetic in its consideration of cryogenic freezing, artificial intelligence, and state surveillance, while its advanced weapons and robot assassins exist in an all-too-imaginable future. Originally published in 1990, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall and before the onset of Cuba’s devastating Special Period, Agustín de Rojas’s magnum opus brings contemporary trajectories to their logical extremes and boldly asks, “What does ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ really mean?”

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein, 1933

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein, 1933

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, published in 1933, is Gertrude Stein’s best-selling work and her most accessible. Consisting of seven chapters covering the first three decades of the twentieth century, the book is only incidentally about Toklas’s life. Its real subject, and narrator, is Stein herself, who reportedly had asked Toklas, her lifelong companion, for years to write her autobiography. When Toklas did not, Stein did. Stein published excerpts of the work in the Atlantic, which occasioned a response from behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner whose essay, “Has Gertrude Stein a Secret?” connected the style Stein employed in the book with her work on automatic writing in Harvard’s psychology laboratories a few decades before. Automatic writing, popularized by the surrealists in the 1920s, was writing that follows unconscious as well as conscious thought of the author. Stein’s writing certainly has some of that element in the Autobiography but on the whole she sticks to telling a story of her life and times in more or less chronological order. That life includes details of her relationships with artists and writers who would become some of the most famous of the twentieth century, including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, Max Jacob, and Sherwood Anderson. Stein’s book is modernist not only because she discusses modernist art and artists but because of how she represents her subject through indirection, paradox, repetition, and contradiction.

Read Along: Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice by Janet Malcolm (2007)

“How had the pair of elderly Jewish lesbians survived the Nazis?” Janet Malcolm asks at the beginning of this extraordinary work of literary biography and investigative journalism. The pair, of course, is Gertrude Stein, the modernist master “whose charm was as conspicuous as her fatness” and “thin, plain, tense, sour” Alice B. Toklas, the “worker bee” who ministered to Stein’s needs throughout their forty-year expatriate “marriage.” As Malcolm pursues the truth of the couple’s charmed life in a village in Vichy France, her subject becomes the larger question of biographical truth. “The instability of human knowledge is one of our few certainties,” she writes. The portrait of the legendary couple that emerges from this work is unexpectedly charged. The two world wars Stein and Toklas lived through together are paralleled by the private war that went on between them. This war, as Malcolm learned, sometimes flared into bitter combat.

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, 1934

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, 1934

The book chronicles the adventures of an American expatriate named Henry Miller during his first year in Paris. Through the use of interior monologue, Miller relates his experiences in the poorer sections of Paris where he lives a life of indigence. The author renders the decadent side of the city in order to portray the whole of society on the brink of self-destruction, but also to allow his protagonist the opportunity to plumb the depths of the dark forces at work in the human personality. Henry has numerous sexual encounters with woman, and later falls in love with and marries Mona, a young American woman who remains a shadowy presence. The city of Paris is beautifully and evocatively presented in this work, which also reveals Miller’s attempt to blend elements of surrealist and naturalist narrative style. Tropic of Cancer is considered by many critics to be Miller’s finest achievement, and it was a profound influence on a number of later writers for whom Miller’s experiments in style and subject proved to be a liberating force.

Read Along: Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri (2021)

Exuberance and dread, attachment and estrangement: in this novel, Jhumpa Lahiri stretches her themes to the limit. In the arc of one year, an unnamed narrator in an unnamed city, in the middle of her life’s journey, realizes that she’s lost her way. The city she calls home acts as a companion and interlocutor: traversing the streets around her house, and in parks, piazzas, museums, stores, and coffee bars, she feels less alone. We follow her to the pool she frequents, and to the train station that leads to her mother, who is mired in her own solitude after her husband’s untimely death. Among those who appear on this woman’s path are colleagues with whom she feels ill at ease, casual acquaintances, and “him,” a shadow who both consoles and unsettles her. Until one day at the sea, both overwhelmed and replenished by the sun’s vital heat, her perspective will abruptly change.

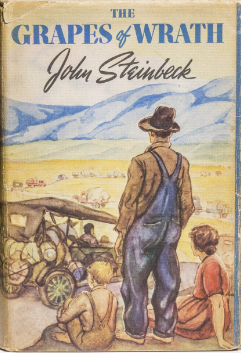

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, 1939

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, 1939

John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939, is a searing social commentary about the plight of poor farmers who have lost their homes and are struggling to survive during the Great Depression. The story follows the Joads, an extended family from Oklahoma, who travel in their makeshift truck to California hoping to find menial jobs picking fruit, only to find themselves unable to fight off starvation. It is an angry, politically powerful book, often considered Steinbeck’s best.

Read Along: Whose Names are Unknown by Sanora Babb (2004)

Sanora Babb’s long-hidden novel Whose Names Are Unknown tells an intimate story of the High Plains farmers who fled drought dust storms during the Great Depression. Written with empathy for the farmers’ plight, this powerful narrative is based upon the author’s firsthand experience. This clear-eyed and unsentimental story centers on the fictional Dunne family as they struggle to survive and endure while never losing faith in themselves. In the Oklahoma Panhandle, Milt, Julia, their two little girls, and Milt’s father, Konkie, share a life of cramped circumstances in a one-room dugout with never enough to eat. Yet buried in the drudgery of their everyday life are aspirations, failed dreams, and fleeting moments of hope. The land is their dream.

(Babb wrote Whose Names are Unknown in the 1930s while working with refugee farmers in the Farm Security Administration (FSA) camps of California. Originally from the Oklahoma Panhandle are herself, Babb, who had first come to Los Angeles in 1929 as a journalist, joined FSA camp administrator Tom Collins in 1938 to help the uprooted farmers. As Lawrence R. Rodgers notes in his foreword, Babb submitted the manuscript for this book to Random House for consideration in 1939. Editor Bennett Cerf planned to publish this “exceptionally fine” novel but when John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath swept the nation, Cerf explained that the market could not support two books on the subject.)

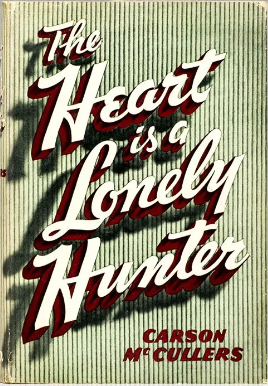

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers, 1940

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers, 1940

This was Carson McCullers’ first novel, published in 1940, when the author was just twenty-three years old. The book introduced themes that stayed with McCullers throughout her lifetime and appeared in all of her works, such as “spiritual isolation” and her notion of “the grotesque,” which she used to define characters who found themselves excluded from society because of one outstanding feature, physical or mental. The story takes place in a small town in the South in the late 1930s. The five central characters cross paths continually throughout the course of about a year, but due to the imbalances in their personalities they are not able to connect with one another, and are doomed to carry on the loneliness indicated in the title. An indication of their lack of coping mechanisms is that the one character that the other four confide their hopes and aspirations and theories to is a deaf mute, who cannot fully understand them nor communicate back to them anything more than his nodding acceptance of what they tell him. Throughout her short career, McCullers’ novels continued to present characters who were cut off from mankind, although, many critics believe, never as successfully as in this first, brilliant stroke.

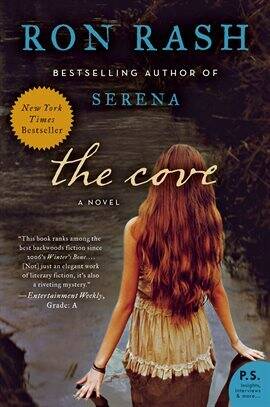

Read Along: The Cove by Ron Rash (2012)

Read Along: The Cove by Ron Rash (2012)

The New York Times bestselling author of Serena returns to Appalachia, this time at the height of World War I, with the story of a blazing but doomed love affair caught in the turmoil of a nation at war. Deep in the rugged Appalachians of North Carolina lies the cove, a dark, forbidding place where spirits and fetches wander, and even the light fears to travel. Or so the townsfolk of Mars Hill believe–just as they know that Laurel Shelton, the lonely young woman who lives within its shadows, is a witch. Alone except for her brother, Hank, newly returned from the trenches of France, she aches for her life to begin. Then it happens–a stranger appears, carrying nothing but a beautiful silver flute and a note explaining that his name is Walter, he is mute, and is bound for New York. Laurel finds him in the woods, nearly stung to death by yellow jackets, and nurses him back to health. As the days pass, Walter slips easily into life in the cove and into Laurel’s heart, bringing her the only real happiness she has ever known.

But Walter harbors a secret that could destroy everything–and danger is closer than they know. Though the war in Europe is near its end, patriotic fervor flourishes thanks to the likes of Chauncey Feith, an ambitious young army recruiter who stokes fear and outrage throughout the county. In a time of uncertainty, when fear and ignorance reign, Laurel and Walter will discover that love may not be enough to protect them.

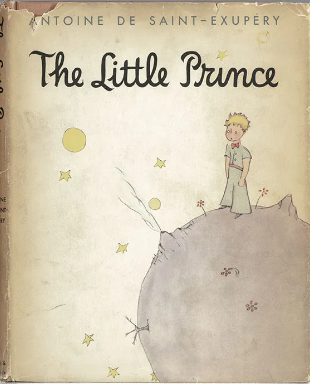

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupéry, 1943

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupéry, 1943

The children’s story The Little Prince, by the French author and aviation pioneer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, was first published by Reynal & Hitchcock in the original French as Le Petit Prince in 1943. Also in 1943, the same publisher brought out an English-language version, translated by Katherine Woods, under the title The Little Prince. The Little Prince tells the story of an encounter between an aviator whose airplane has crashed in the desert and an enigmatic visitor from another planet, the little prince of the title. The little prince’s account of his journey to Earth via other planets and his impressions of the inhabitants becomes an allegory of human nature. An allegory is a representation of an abstract or spiritual meaning through concrete or material forms. The novel’s themes include spiritual decay and the importance of establishing bonds of love and responsibility with other beings.

Read Along: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy (2019)

From British illustrator, artist, and author Charlie Mackesy comes a journey for all ages that explores life’s universal lessons, featuring 100 color and black-and-white drawings. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” asked the mole. “Kind,” said the boy. Charlie Mackesy offers inspiration and hope in uncertain times in this beautiful book, following the tale of a curious boy, a greedy mole, a wary fox and a wise horse who find themselves together in sometimes difficult terrain, sharing their greatest fears and biggest discoveries about vulnerability, kindness, hope, friendship and love. The shared adventures and important conversations between the four friends are full of life lessons that have connected with readers of all ages.

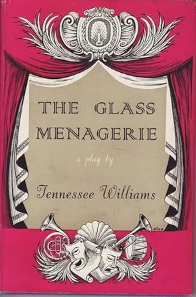

The Glass Menagerie [Play] by Tennessee Williams, 1944

The Glass Menagerie [Play] by Tennessee Williams, 1944

The play is set in St. Louis during the Depression. The Wingfields are a family struggling through difficult financial and emotional times. Amanda Wingfield, mother to Laura and Tom, is an aging Southern belle whose husband has left her and who lives in the past, obsessed with her former beauty and popularity. Laura is crippled and withdrawn. Her physical deformity parallels her emotional impairment, for she is too fragile and weak to deal with the outside world. Like her mother, she lives in a world of fantasy, as the keeper of a collection of glass animal figurines, the “menagerie” of the title. Tom is an aspiring writer, frustrated with his job in a shoe factory. Amanda urges him to bring home a suitor for Laura, a “gentleman caller,” suitable for marriage. Tom agrees to bring home his friend Jim O’Connor, and Amanda busies herself with the preparations. Jim and Laura are drawn to each other; after dinner, they dance and accidently run into Laura’s glass collection, breaking one of the pieces. As they stoop to pick it up, they kiss. However, the possibilities of the encounter are dashed when Jim reveals that he is engaged and can never return to the Wingfields. Amanda is enraged with Tom, who storms out of the house. In the play’s conclusion, he has left his family, determined to be a writer, yet haunted by his deception.

Read Along: August: Osage County by Tracy Letts (2008)

One of the most bracing and critically acclaimed plays in recent history, August: Osage County is a portrait of the dysfunctional American family at its finest–and absolute worst. When the patriarch of the Weston clan disappears one hot summer night, the family reunites at the Oklahoma homestead, where long-held secrets are unflinchingly and uproariously revealed. The three-act, three-and-a-half-hour mammoth of a play combines epic tragedy with black comedy, dramatizing three generations of unfulfilled dreams and leaving not one of its thirteen characters unscathed.

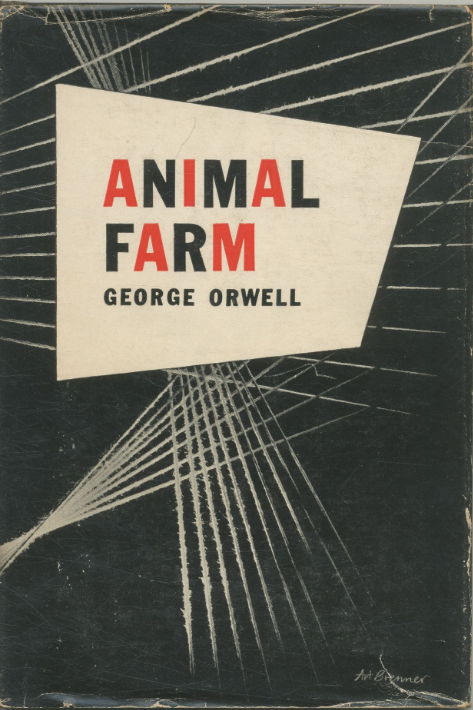

Animal Farm by George Orwell, 1945

Animal Farm by George Orwell, 1945

Animal Farm by George Orwell (1903-1950) is one of the most famous allegorical novels of the twentieth century. It illustrates the growth of authoritarianism in the Soviet Union through a story about barnyard animals who decide to revolt against their human masters in order to create a utopian “animalist” state. Though he completed it in 1944, Orwell initially had trouble finding a publisher for the book, in part because of its implicit criticism of the Soviet Union, a crucial British ally at the time. Animal Farm was eventually published in August 1945, three months after the end of the war in Europe. It has been lauded as a classic of English prose, renowned for its masterful use of parody and language, as well as its exploration of human nature and social systems.

Read Along: Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo (2022)

NoViolet Bulawayo’s bold new novel follows the fall of the Old Horse, the long-serving leader of a fictional country, and the drama that follows for a rumbustious nation of animals on the path to true liberation. Inspired by the unexpected fall by coup in November 2017 of Robert G. Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s president of nearly four decades, Glory shows a country’s imploding, narrated by a chorus of animal voices that unveil the ruthlessness required to uphold the illusion of absolute power and the imagination and bulletproof optimism to overthrow it completely. By immersing readers in the daily lives of a population in upheaval, Bulawayo reveals the dazzling life force and irresistible wit that lie barely concealed beneath the surface of seemingly bleak circumstances. Although Zimbabwe is the immediate inspiration for this thrilling story, Glory was written in a time of global clamor, with resistance movements across the world challenging different forms of oppression. Thus it often feels like Bulawayo captures several places in one blockbuster allegory, crystallizing a turning point in history with the texture and nuance that only the greatest fiction can.

Bestselling Fiction in the U.S. 1930-1945

Cimarron by Edna Ferber

The Good Earth by Pearl Buck

The Good Earth by Pearl Buck

Magnificent Obsession by Lloyd C. Douglas

So Red the Rose by Stark Young

Green Light by Lloyd C. Douglas

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

How Green Was My Valley by Richard Llewellyn

The Keys of the Kingdom by A. J. Cronin

The Song of Bernadette by Franz Werfel

The Robe by Lloyd C. Douglas

Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith

Forever Amber by Kathleen Winsor