Since ancient times rulers and scholars have made efforts to organize and store records for posterity. What might be considered the very first “libraries” were simply temple and palace rooms that were used to house tablets, scrolls, and other official and sacred documents. Over time with the invention of the modern book, such storage rooms evolved into what would become libraries as we know them today. The word “library” in fact comes from the Anglo-French word librarie, which means a collection of books or a bookshop. The word in turn is derived from the Latin word libarius (concerning books) and libarium (chest for books), and so when people think of libraries, they imagine a place filled with books. And why wouldn’t they? The word essentially means books!

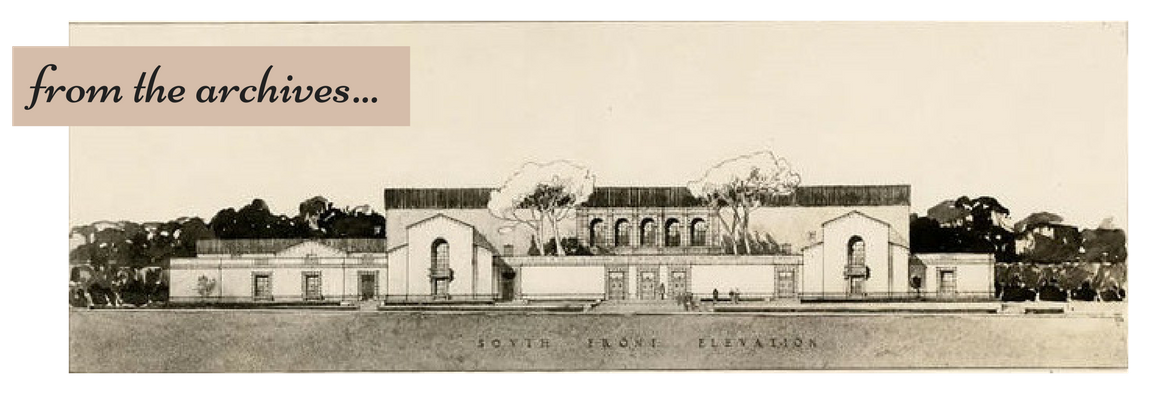

Libraries are indeed treasure troves of wonderful books, and the Pasadena Public Library is no exception. But some libraries, particularly those with a long history, have amassed more than just books in their collections. Beyond the stacks of Pasadena’s Central Library are objects that might be more at home in a museum. These are artifacts that tell a story about their creator, memorabilia that recall days gone by, and other miscellanea that bear the history of California or Pasadena. How items in this motley collection have come to the library or whence they came is both known and a mystery. Some have been acquired by the library over the decades, but many others were donations whose provenance has been lost to time. A few of these items were once cataloged, meaning they were searchable using the card catalog, but many others were never officially a part of the library’s collection. For decades they’ve sat hidden from view, stored away in various parts of the library. Like books, they serve as vessels of information, knowledge, stories, memories, and culture. And by virtue of their historical value and their link to the past, they are part of the Pasadena Public Library’s renown and most treasured collection of California and Pasadena history.

Housed in the Centennial Room at the Central Library, this special collection includes books, magazines and newsletters, newspapers and news clippings, oral history transcripts, pamphlets, scrapbooks, yearbooks, historical and rare books, city directories, historical maps, photographs, ephemera, city reports, and many other types of city documents. And among these items that one would expect to find in such a collection are some of the library’s most unique and fascinating objects that offer a glimpse into the past. For the first time, some of them are on exhibit at the Hill Avenue Branch.

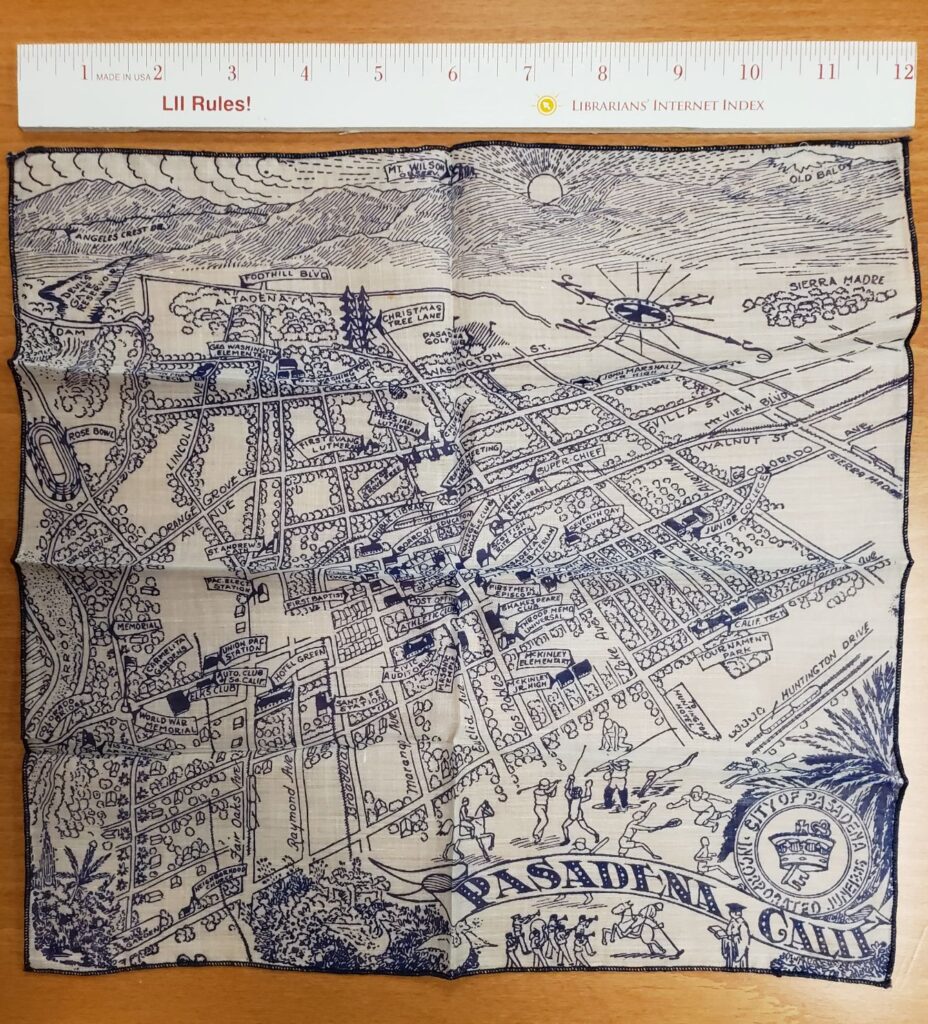

Souvenir handkerchief

Souvenir handkerchiefs were quite popular in the early 20th century, especially during the 1920s when automobiles became widely available to many people who could now go on road trips and visit various cities throughout the United States. Travelers would often buy handkerchiefs like this one as gifts or to show folks back home where they went. Like postcards, they usually had depictions of landmarks, local attractions, landscapes, or flora and fauna of the city or state where they were purchased. Souvenir handkerchiefs remained popular well into the 1950s. This handkerchief showing a map of Pasadena is probably from 1932 (the earliest) to 1938 (the latest). The date range is based on some landmarks, notably the Civic Center, which opened in 1932, and a sign pointing to Busch Gardens, which closed in 1938.

We received this souvenir handkerchief anonymously in the mail in late 2021. No information about it or who sent it was included other than the postal marking on the envelope that indicated it might have come from Iowa.

Tule Lake flowers

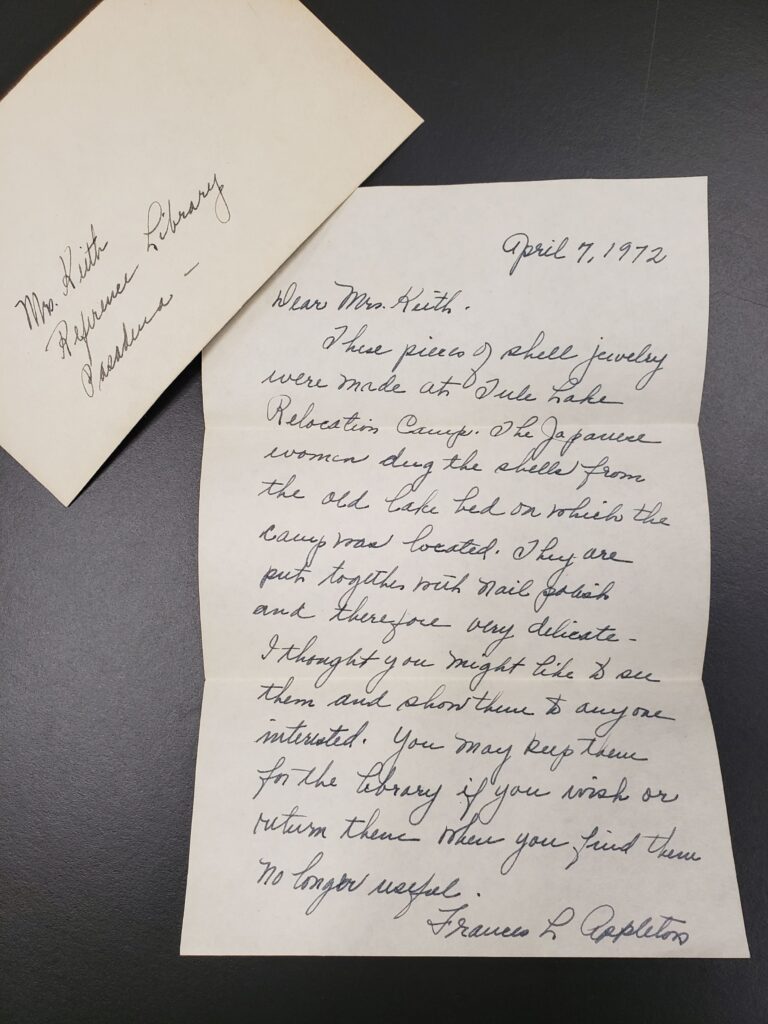

Shortly after the United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which established internment camps to house residents of Japanese descent. These camps were located in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. The largest of these camps was the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Northern California. Originally called Tule Lake Relocation Center when it opened on May 27, 1942, the camp was used to incarcerate Japanese Americans living on the West Coast but a year later became a maximum-security segregation center to detain those who were thought to be “disloyal” to the U.S. and potential enemies of America. Life at this camp was harsh, and the landscape and climate of the area made it even more so. Yet, despite the difficult conditions, the incarcerated inhabitants tried to make life as normal as possible. They celebrated traditional Japanese festivals, held dances, and played baseball. They passed the time by making jewelry and ornaments using everyday items at home and things they found by Tule Lake. These flowers were handcrafted using shells dug up from the lakebed and pieced together with nail polish. They were made sometime between 1942 and 1946, the years in which the Tule Lake Segregation Center was in operation. They are exquisite ornamental pieces that in many ways symbolize the delicate normalcy of life in the camp.

The shell flowers were donated to the library in 1972 by Francis Appleton.

Sewing kit

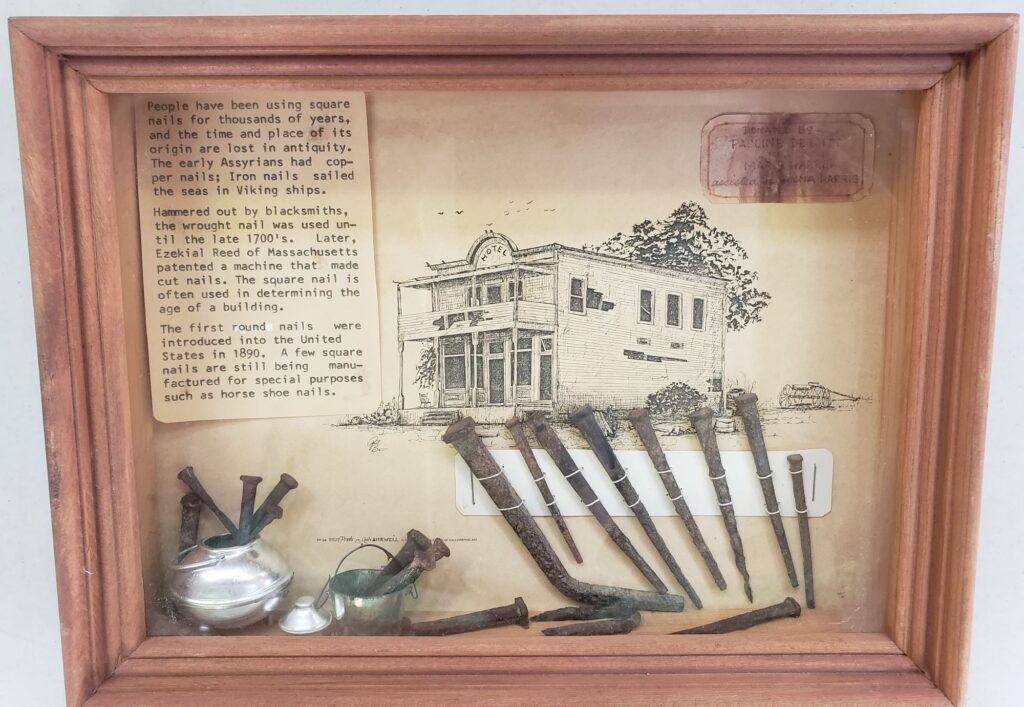

Many people take for granted the convenience of buying ready-made clothing at a store. Such a luxury didn’t exist prior to 1920 when people had to make and mend their own clothes. This sewing and embroidery kit was once owned by Bertha Elterich, an early Pasadena resident. It includes a fabric scissor with holster, a smaller embroidery scissor, thimble, needle basket, awl, and a small mix of buttons. We’re not quite sure what the glass object in the center is. It looks a bit like a miniature lamp. The kit dates from about 1900 to 1945 and was donated to the library by Pauline DeWitt and Marie Harris who created this miniature display. On the back is a 1981 date, and it’s possible that is the year the donation was made.

Early nails

Nails have been around for thousands of years, with the earliest dating back to 3000 BCE. Early nails were individually wrought by hand by pounding a small piece of metal into a shape that was flattened on the sides and resembling an elongated wedge. It was a time-consuming process until the late 1700s when machines could mass produce them by cutting sheets of metal into individual nail pieces. Round nails, also known as wire nails, were introduced in 1890 and were faster and cheaper to produce and have since become the predominant type of nail used. Because of their superior holding power, square nails still find some usage in the construction industry today. This miniature display of early square nails was created by Pauline DeWitt and Marie Harris who donated it along with the sewing kit to the library.

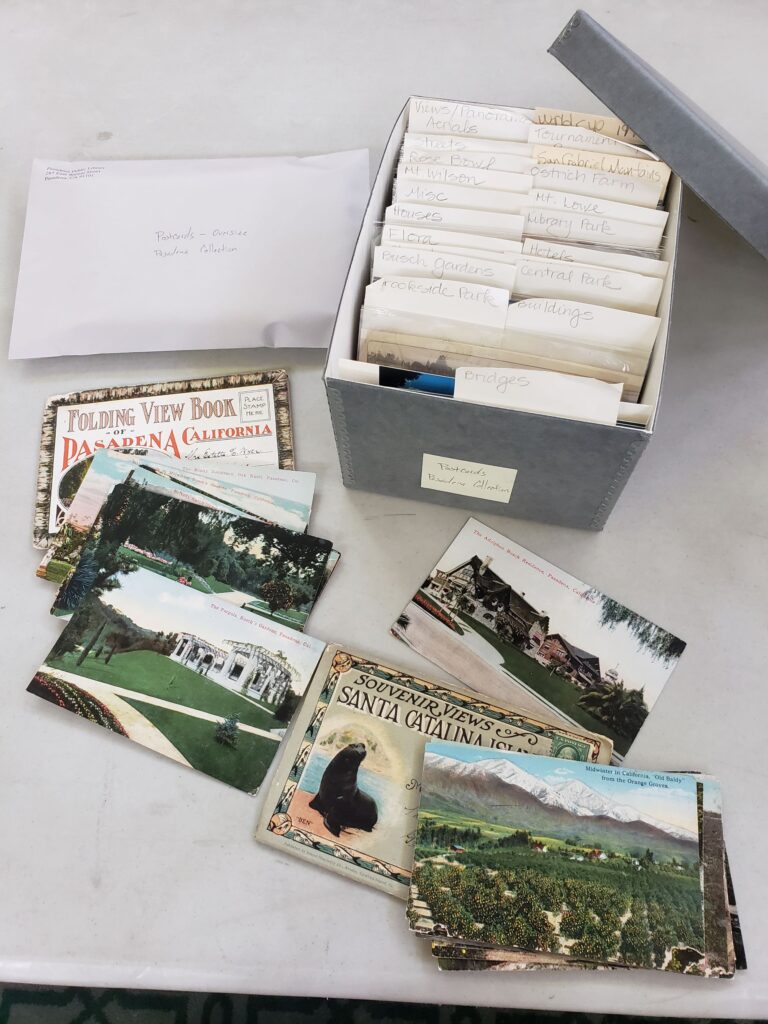

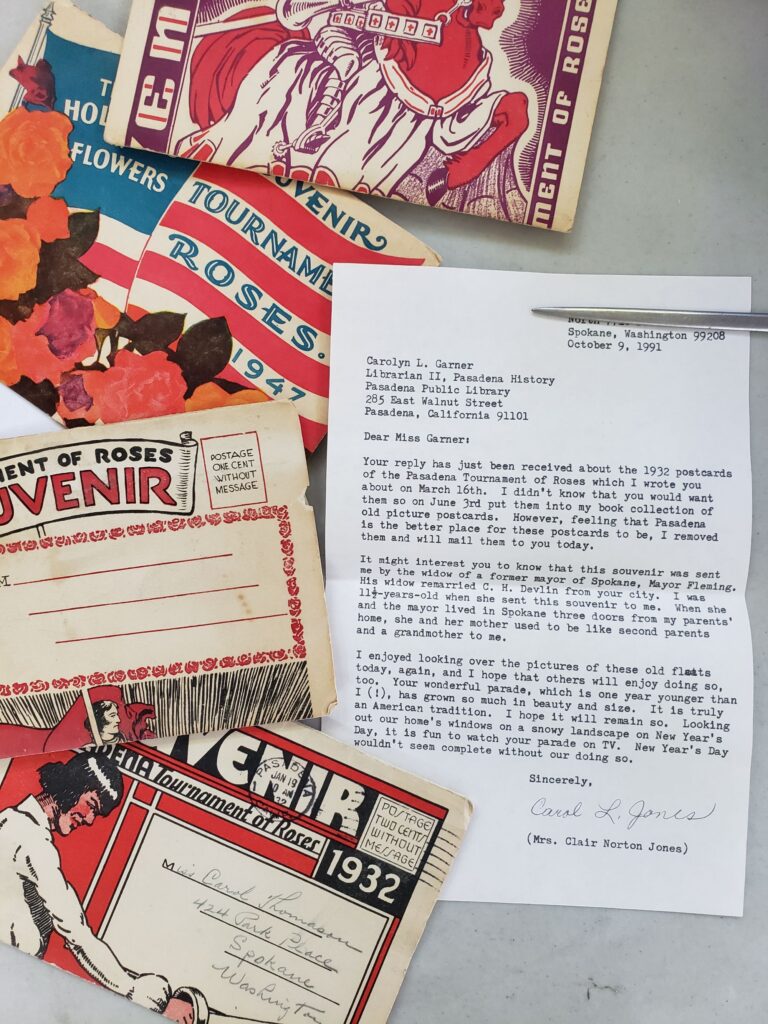

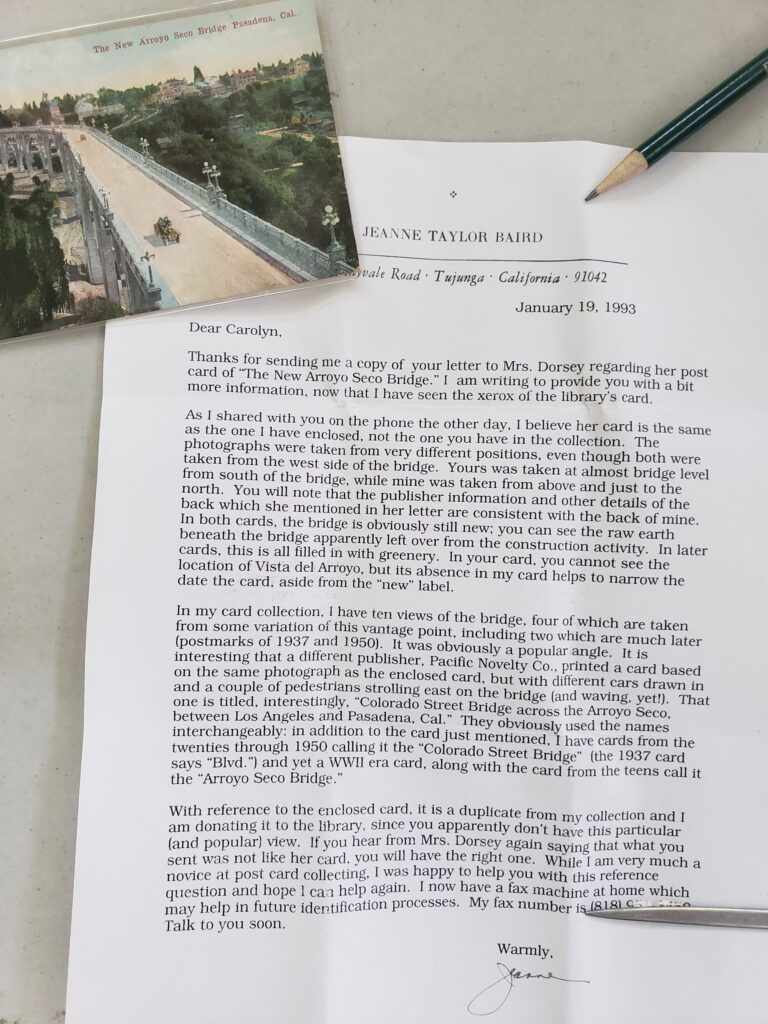

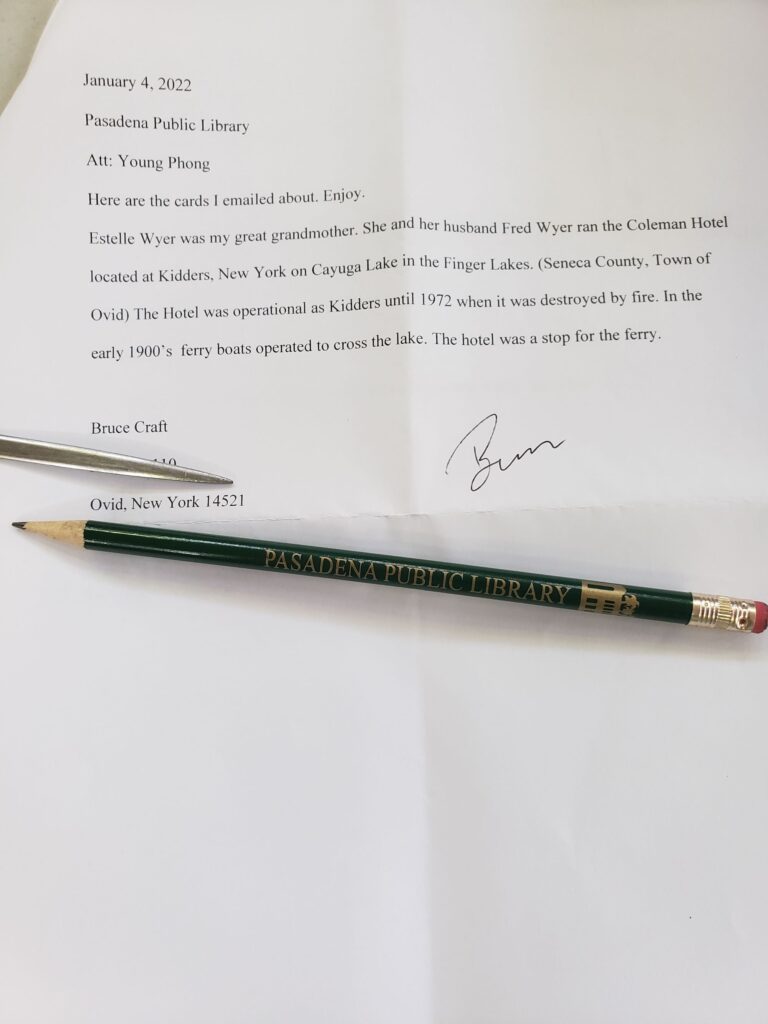

Postcard collection

Postcards gained popularity at the end of the 19th century, but it was the early decades of the 20th century that saw their usage soar. They were cheap and fun to send. Often sold at souvenir shops, they depicted interesting destination points and the characteristics of a location. Before Instagram, postcards were a quick way to share an experience with family and friends who weren’t able to be there. Deltiology, the official name for postcard collecting, is one of the biggest and most popular hobbies in the world. Because they offer a wealth of information about architecture, culture, and city landmarks that are period specific, postcards are a great visual resource for those interested in local history research. Not many may know that some libraries have a postcard collection that people can use to study the past. The Pasadena Public Library has a small collection that contains postcards of Pasadena with pictures of notable structures, architecture, neighborhoods, landmarks, natural sceneries, and the Rose Parade as well as a few postcards about other California cities. They range in date from the early 1900s to the 1990s and were collected over the years, mostly through donations. The postcard collection represents the different types of research resources that the library has in its special collections.

Stereoscope and image cards

Stereoscopes were popular viewing devices in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They were mainly for entertainment but had educational value as well. Many libraries at the turn of the century had them in their children’s room. This stereoscope and image cards belong to the Pasadena Public Library and were probably once used by children in the Boys and Girls Library. A stereoscope works by placing an image card with two very similar photos in front of it. The two photos taken at slightly different angles appear 3-dimensional when viewed through the stereoscope. The library opened a children’s room in 1900, and this stereoscope and the collection of image cards are probably from the early 20th century.

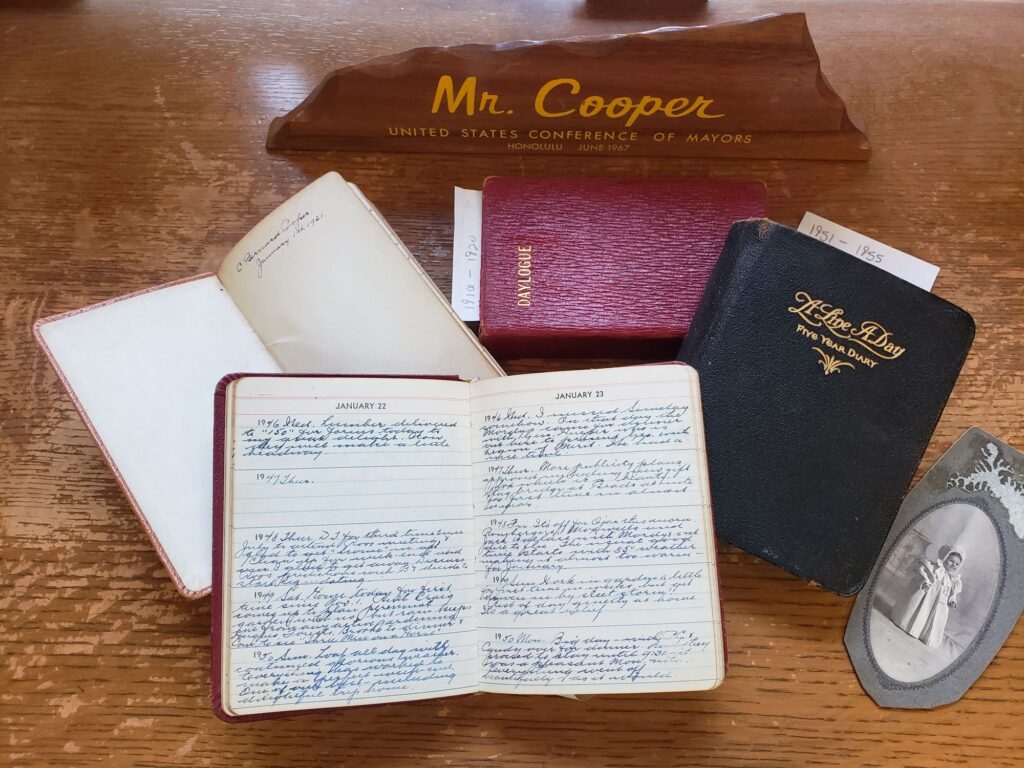

Cyril Bernard Cooper collection

C. Bernard Cooper (abt. 1900–1971) was mayor of Pasadena from 1968 to 1970. He was a manager of Bullock’s department store before going into government. He began his political career on the Pasadena Board of City Directors in 1963, and five years later became mayor. During his time in office, he improved the city’s infrastructure by resurfacing damaged roads and widening sections of streets, moving utility lines underground, installing more drain lines, and adding new traffic signals and safety lighting. While he was mayor, the Police Department received funding for two police helicopters, and the department’s Human Relations division was strengthened to develop a closer and more harmonious relationship with the city’s residents. Cooper was very active in keeping a diary and scrapbooking during his early adult life and well into his later years. His diaries along with some family albums, scrapbooks, and other personal keepsakes were donated to the Pasadena Public Library by his family after his death in 1971.

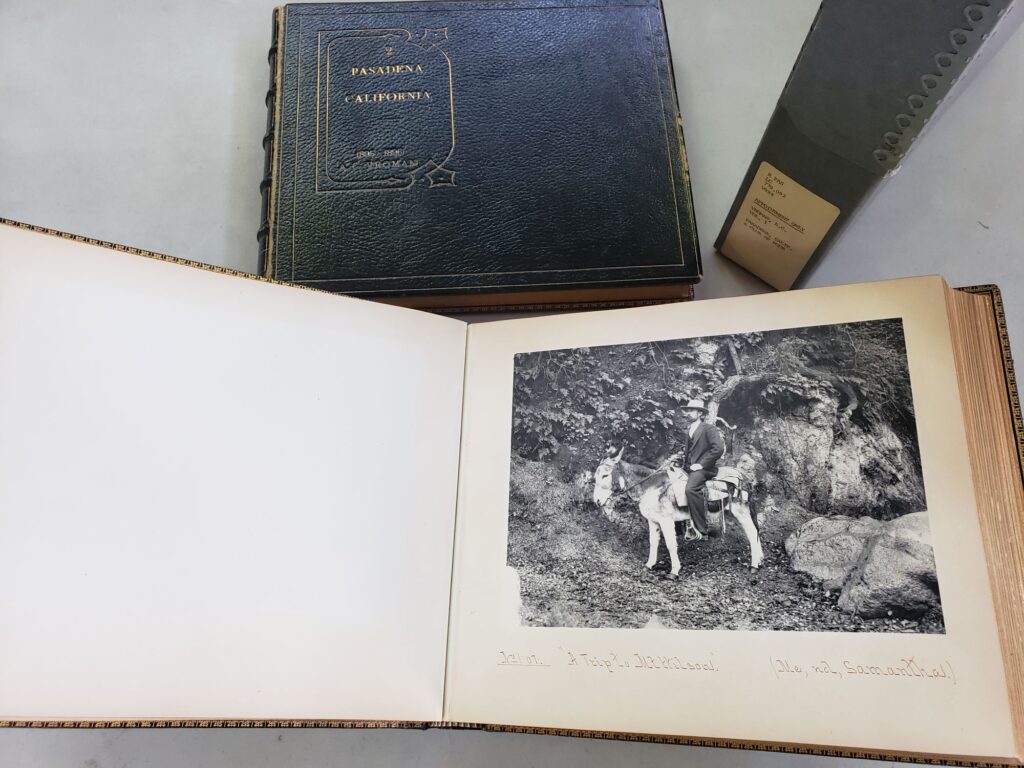

A.C. Vroman photograph collection

Adam Clark Vroman (1856–1916) was an accomplished amateur photographer in Pasadena. He was also a rare book collector and the owner of a shop that sold books, stationery, and photography supplies. The shop still exists today as Vroman’s Bookstore. His early interest was photographing the landscape and architecture of California, but between 1895 and 1904, he traveled throughout southern California then to Arizona and New Mexico to photograph and document the landscape and Indians of the American Southwest.

The Pasadena Public Library houses the most complete collection of Vroman’s photographs at the Central Library. The library has sixteen bound volumes of his platinotype prints and over 2,000 of his glass plate negatives, all of which were donated to the Pasadena Public Library after his death.

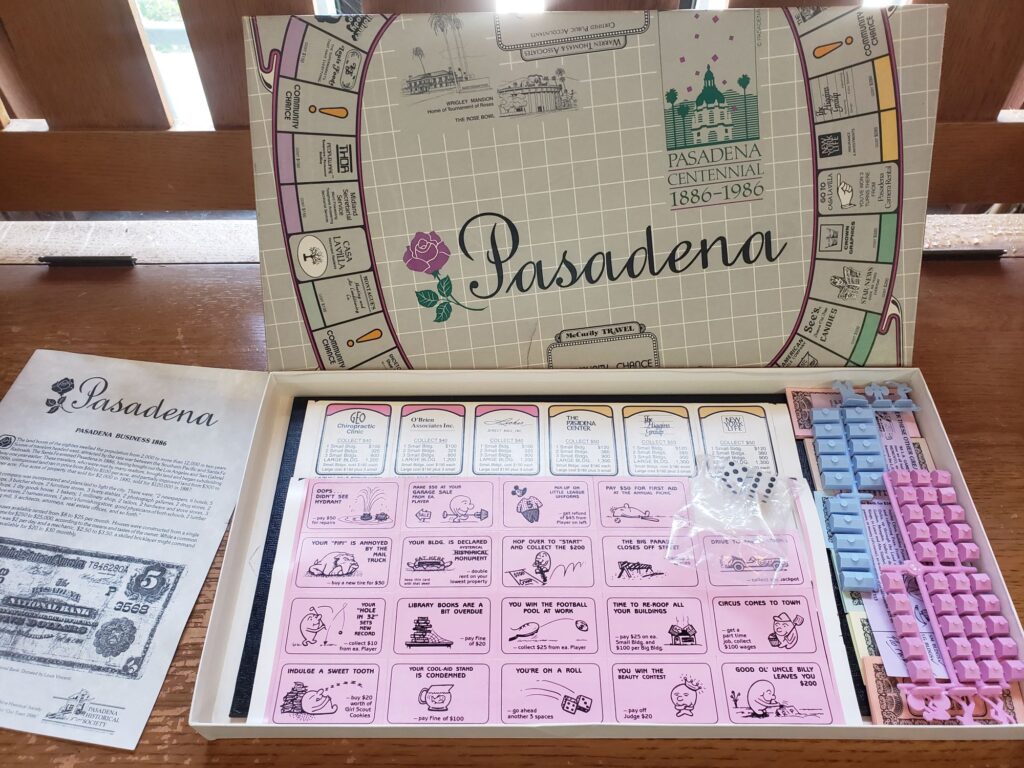

Pasadena Centennial board games

Pasadena celebrated its centennial in June 1986. It was a huge celebration for the city and its residents who came to City Hall for the official ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary of Pasadena being incorporated as a city in 1886. The event included a panoramic shot of attendees in front of City Hall and the release of hundreds of balloons. Putting together the event was a collaboration between the city and many community organizations, which helped raise funds for the centennial celebration. Along with shirts, mugs, and pins, the sale of board games like the Pride of Pasadena and Pasadena Monopoly raised thousands of dollars. These games mark a historic moment in Pasadena history, and they are just some of the more interesting items about the Crown City in the Centennial Room.

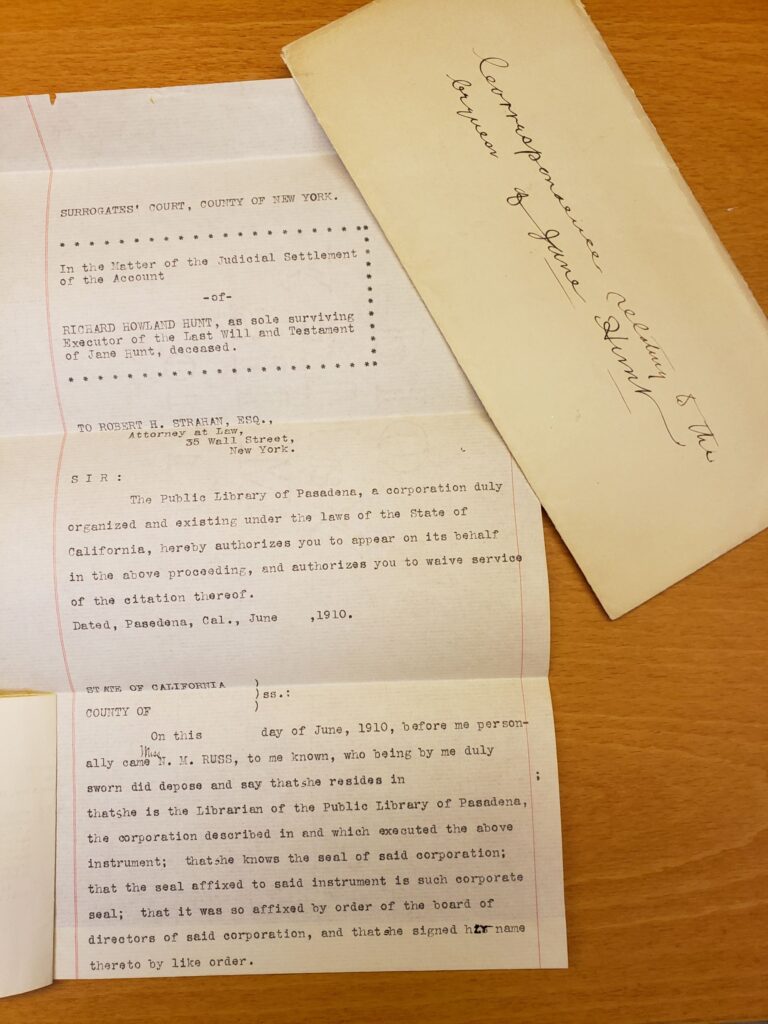

Jane Hunt collection

Jane Hunt was born in Brattelboro, Vermont, on Aug. 31, 1822. She was the eldest child of Jonathan Hunt, a U.S. Congressman, and Jane Maria Leavitt Hunt. Like her mother, she was very artistic and a prolific writer growing up. Although she did not have formal art training, like her more famous brother William Morris Hunt, she took art classes and honed her talent at his art studio. Hunt was active as a painter in southern California from 1883 to 1905. She is best known for her watercolor paintings of the California missions and the area around Los Angeles. She never married and died in New York City in 1907. During her time in California, she created over 100 watercolors, which are now owned by the Pasadena Public Library. These paintings have been digitized and can be viewed on the Pasadena Digital History Collaboration website.