Contributing writers: AnnMarie Kolakowski and William Gerber

February is Black History Month, which celebrates the accomplishments and contributions African Americans have made throughout U.S. history. It also honors and pays tribute to the generations of African Americans who have struggled and fought for equality and basic human rights. But just as important, Black History Month is an opportunity to understand and learn more about the African American experience and Black histories that go beyond stories of slavery and racism and highlight the many achievements of Black people in the United States and elsewhere.

Black History Month is the legacy of Carter G. Woodson, a son of former slaves who went on to earn a PhD at Harvard University in 1912. A historian by training, he helped establish the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, an organization whose mission was and continues to be the study and preservation of Black life and history. In 1926, the group started Negro History Week to encourage schools and many social and civic organizations to study Black history as well as to celebrate the many contributions African Americans have made to America’s social, economic, and cultural development. The second week of February was chosen because it corresponds with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. In the years following, the event gradually spread to other cities across the United States and experienced a resurgence during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month in 1976, and since then every February is a month full of events, activities, and discussions that honor and focus attention on African Americans and their history.

As the nation begins its celebration of Black History Month, Pasadena, too, celebrates its own Black history and the people who have contributed to the Crown City’s rich history and traditions. They are the sons and daughters, movers and shakers, ordinary citizens and icons who have helped make Pasadena the beautiful and esteemed city it is today. Here are ten notable Pasadenans who have made contributions in the area of medicine, literature, music, sports, government, law, education, and civil rights. This is by no means a complete list, but we hope it inspires you to learn more about Black history in Pasadena. Stop by any of the Pasadena Public Library branches and check out the displays for Black History Month and ask about the resources we have on African Americans in Pasadena.

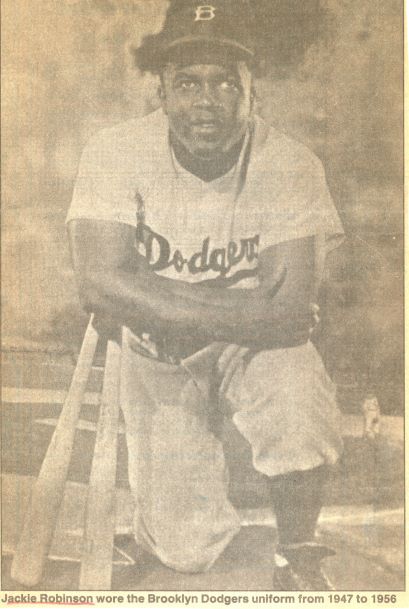

Jackie Robinson

Jackie Robinson was one of America’s greatest baseball players. His historic debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, made him the first African American player in Major League Baseball during a time of segregation. Born in Cairo, GA, he spent much of his formative years in Pasadena where his athletic talents came to light. He was quickly recognized as a star athlete in the local schools he attended and later at Pasadena Junior College (now Pasadena City College) and UCLA. In addition to his much celebrated athleticism, he is also lauded for his civil rights work and his legacy fighting for racial equality. Robinson witnessed and experienced racial discrimination growing up in Pasadena and throughout his life while playing professional baseball, but he remained undaunted and challenged racist attitudes and policies that sought to disenfranchise African Americans. He has inspired a generation with his courage, strength, and determination in the face of racism and injustice. His groundbreaking career and social advocacy have left a lasting impact, and we remember him not only for being a great baseball player but also for being a powerful civil rights activist.

Mack Robinson

Matthew MacKenzie Robinson, better known as Mack, was the older brother of baseball legend Jackie Robinson and was a great athlete in his own right. He was a rising star in the track and field team at Pasadena Junior College before he became an Olympic medalist in 1936, when he won the silver medal in the 200-meter dash during the Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany. Unlike Jackie, Mack spent much of his life in Pasadena and did much to help improve the city he loved. He was involved in neighborhood improvements and played a big role in ridding Northwest Pasadena of crime beginning in the 1970s. He was a youth advocate and a staunch supporter of education and lobbied tirelessly for better educational and recreational resources and facilities to meet the intellectual and social needs of Pasadena’s young citizens. Much like his younger brother, he’s remembered for both his Olympic accomplishments and for his advocacy and work in improving Pasadena and its many communities.

Loretta Thompson-Glickman

Loretta Thompson-Glickman became the first Black woman mayor of Pasadena in 1982, but she had a few other firsts before this one. In 1977 she was the first Black woman elected to the Pasadena City Board of Directors; in 1978, she was the first Black woman to become a member of the Tournament of Roses Association; and in 1980, she was the first Black woman to become Vice-Mayor of Pasadena. These were huge accomplishments for Glickman but monumental milestones in equality and race relations for Pasadena. Before she entered public service, Glickman was a professional jazz singer and a teacher, professions that helped her easily connect with people in her political career. In her various civic roles, she made local government more accessible to residents and her active involvement in the community she served inspired them to be more engaged in civic affairs. She shattered the proverbial glass ceiling with her many accomplishments, and she remains a great model for young women, particular women of color.

William Prince

Pasadena is home to many notable Black families whose histories go back to the city’s very early years. Early pioneers such as the Prince family headed west from Tennessee to stake out a new and better life. It was William Island Prince, the youngest of three sons, who first moved to Pasadena in 1884 to seek work. At the age of 13 he began working in the city as a dishwasher. His father (Samuel), brothers (Frank and Charles), and stepmother (Penelope Weimar) joined him in 1886 and they became the second black family to live in Pasadena. Over the years, William’s hard work and commitment to his family and the Black community helped his family establish their place in Pasadena’s rich history. He was politically active in the Republican Party and the Afro-American Congress, of which he became state president in 1904. In 1901 he served on the Rules and Order of Business Committee for the nonpartisan nominating committee for the first publicly elected Mayor of Pasadena. Besides his involvement in several commercial enterprises, he also made extensive real estate investments in the city. He is perhaps best remembered as an active and popular minister of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Pasadena, which he helped found. He and his wife, Ruby Edmonson, had eight children, all of whom graduated from Pasadena High School. A family history compiled in 1983 details the accomplishments of William and his brothers Frank and Charles and their children in the fields of education, administration, and music.

Benjamin F. McAdoo

Benjamin F. McAdoo came from a pioneering family that has a long history in Pasadena. His parents, Booker and Carrie McAdoo, and their three children moved to Pasadena from Arkansas in 1900. They opened a restaurant upon arriving and later opened a grocery store on 53 S. Fair Oaks Ave. After Booker died, Carrie closed the store and opened a bigger one on 670 S. Fair Oaks Ave. Ben and his two sisters helped with the family business, which catered mainly to Blacks and other minorities living in the surrounding neighborhoods. The McAdoos was an industrious and enterprising family that prospered during a time when Blacks were afforded little opportunity to do well in life. Growing up in Pasadena almost all his life, Ben saw the many changes that Pasadena went through over the years. In interviews he gave before his death in 1984, he talked about segregation and the restrictive neighborhood covenants that prevented Blacks from living in certain communities, but he also fondly recalled his boyhood playmate George S. Patton, who he said was a “regular fellow with us poor boys.” In his later years he was called the “dean” of Pasadena’s Black history and was a master storyteller who recounted his family’s life and experience growing up in Pasadena. He was a rich source of information for those who wanted to learn about Pasadena’s history but most importantly the histories of African Americans who grew up in the Crown City.

Elbie Hickambottom

Elbie Hickambottom was just one year old when his family moved to Pasadena from Okmulgee, OK. He attended Pasadena public schools and after high school enrolled in Pasadena Junior College. His education was interrupted when WWII started, and he joined the Army where at the age of 19 he became one of the youngest first sergeants in Europe. After his military service, he started working for the Pasadena Redevelopment Agency as the director of Relocation and Property Management in 1967. He oversaw programs that provided assistance to displaced families and small businesses. In 1971, he and his wife, Dolores, established the Pasadena Education Foundation, which continues to this day to encourage greater involvement and support for public education from the community. Following the 1976 landmark case Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, which required the Pasadena Unified School District to implement busing and thus end the segregation of schools, he became the first African American elected to the PUSD Board of Education in 1979. During his tenure on the Board, Hickambottom championed academic excellence and continuously pushed for equal access to a good education for all students, but he was particularly a strong voice for disadvantaged and minority students. The Elbie J. Hickambottom Board Room where the School Board meets was named in his honor.

Octavia Butler

Octavia E. Butler was born in Pasadena in 1947 and lived in Pasadena and Los Angeles for most of her life before moving to Washington where she died in 2006. She was raised by her mother, a widowed housemaid, and her grandmother. From a young age Butler was exposed to the harsh realities faced by African Americans and saw her mother treated badly by her white employers. Through it all, however, she also absorbed her mother’s strong work ethics, which became a powerful aspect of her own character and an important part of her success as a writer.

Despite a strict upbringing and a reading disability, Butler had a rich imagination and a hunger for books, and as a child she loved visiting the library to read fantasy and write. She showed great determination to become a writer from a very young age, asking her mother for a typewriter. She graduated from John Muir High School in 1965 and then started working during the day and attending classes at Pasadena City College at night, getting her Associate’s Degree in 1968. Her first income as a writer was from a short story contest she won as a freshman at PCC.

Butler would later go on to win many awards and a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, but that financial success only came after many years of grueling work in obscurity. She used to rise every day at 2 a.m. so that she could get some writing done before going to work at multiple jobs, including a telemarketer, a potato chip inspector, and a dishwasher. To get to her jobs, she was limited to walking and riding the bus, but she used that time to think and write, recording her “walk thoughts” in a notebook. She treated everything as grist for the mill, and no matter how difficult things got, she kept writing.

Butler had a lifelong passion for science fiction, but she was dismayed to never find any African American characters apart from small, unimportant and often feeble-minded characters. “I wrote myself in,” she told the New York Times in 2000, “since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.” She studied with science fiction writer Harlan Ellison, who introduced her to other writers and pushed her to go for other opportunities like the six-week Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop—where later in life she would teach writing to aspiring writers.

Throughout the 1970s Butler was hard at work on a series of books called the Patternist series, starting with Patternmaster published in 1976. With the success of this series she was able to stop doing her other jobs and live on her writing. In 1979 she wrote Kindred, which was the book that the Pasadena Public Library read for its One City, One Story program in 2006.

In the 1980s Butler got two Hugo Awards for “Speech Sounds” (a short story) and Bloodchild (a novelette). She also wrote the Xenogenesis trilogy which was based on research she did in the Amazon rainforest. But her real rise to fame in American literature came in the 1990s with her 1993 book The Parable of the Sower. This book earned her the notice of the MacArthur Foundation, which gave her a Genius Grant in 1995. Her next novel, The Parable of the Talents, won a Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1998.

Butler suffered from writer’s block, depression, and high blood pressure, and she died when she was 58. She left behind a legacy of a dozen novels and a wealth of strong black female protagonists in a genre usually dominated by white characters and white male authors. Perhaps it was her intimate familiarity with racism and social injustice that made her so adept at creating believable dystopias. Her work was as sensitive and nuanced as it was troubling and thought-provoking, promoting empathy and discussion. About her book Kindred she said, “I wanted to write a novel that would make others feel the history: the pain and fear that Black people have had to live through in order to endure.” Instead of being an anomaly in science fiction literary history, Octavia Butler helped redefine science fiction with stories that offer an important and unique perspective that transformed the genre into something even more powerful and universal.

George Garner

George R. Garner was a musician, singer, actor, educator and advocate for the study of African American music history. He was born in Chicago in 1906 and graduated from Chicago Musical College. He was the first African American singer to solo with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Despite his father’s objections to him pursuing a career in music, young George Garner was able to earn enough money to support his wife, Netta Paullyn Garner, and buy a house. In 1924 they had a daughter, Paullyn.

Garner’s talent gained him patronage by wealthy people in the United States and abroad. In 1929 he went to England to study music for three years, becoming a soloist with the London Symphony Orchestra. He toured Britain and Ireland before coming back to the United States and settling in Pasadena. His talent was immediately noted when he moved here to Pasadena in 1933. Within a year he had become the music director of Friendship Baptist Church and the first African American man to star in a leading role in a Pasadena Playhouse production—Finder’s Luck by Alice Haines Baskin.

Passionate about African American music history, Garner got a degree in music education at USC and became the first African American teacher in Pasadena. He founded a choral group called the George Garner Negro Chorus. In 1937, he founded the Pasadena Association for the Study of Negro Life and History so that African-American musical traditions could be preserved. The association provided a musical library with the goal of preserving spirituals and also gave musicians rehearsal space. It was set up in a studio at 470 Blake Street (no longer standing). He was the regional director of the National Association of Negro Musicians. He became a music critic and arts editor for the Los Angeles Sentinel in the 1950s. And in 1959 he was honored by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors as the executive vice president of the George Garner Music Research Center of Pasadena.

In a Los Angeles Times article published in 1933, he said: “Singing, I can express my gratitude for so much that has been done for me.” He was described in that article as having a “quiet, grave attitude toward his music” but clearly found a great deal of joy in music too, and he wanted to share that joy with the world, especially with the African American community in Southern California. In pictures we can see him beaming (“The great George”) standing beside his wife Netta, who often accompanied him on piano as he sang German lieder, classical and modern songs, and African American spirituals.

Garner died in 1971 but left behind a legacy of promoting African American musicianship and music study in Pasadena and a long, loving marriage fueled by that love of music.

Edna Griffin

Dr. Edna Griffin was the first Black woman physician in Pasadena, though she is also especially remembered for her work for social justice in Pasadena. She was born in 1905 in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where her father, a Methodist minister, died in 1918 of the flu. She dreamed of becoming a doctor and wanted to go to USC Medical School, but in the 1920s USC didn’t accept Black medical students. So she studied, lived and worked for many years in the Southeast and Midwest. She got her medical degree at Meharry Medical College, an HBCU in Nashville, and interned at John Andrew Hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. After working for a while in Evansville, Indiana, she finally moved to Pasadena in 1935.

As a doctor and business owner, Griffin became the first Black member of the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce. She saw many injustices in Pasadena and felt it important to work for a fairer community for all. She became involved with the Pasadena YMCA and the Pasadena Chapter of the NAACP, where she served as its first woman president from 1939 to 1947. She is credited with saving the land that became Brenner Park from development, opening restaurants to serving African Americans, and most notably the hiring of five African Americans to previously white-only positions—two positions being those of policeman and fireman.

Throughout the 1940s during her tenure as president of the Pasadena NAACP, she filed more than 20 lawsuits against businesses and restaurants for discrimination. She led a successful fight for civil rights here in Pasadena long before the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s. One of her most notable wins was the lawsuit against the city for segregating the Brookside Plunge.

The Brookside Plunge (later demolished and rebuilt as the Rose Bowl Aquatics Center) was built in 1914 and on most days of the week only whites could use it. Nonwhites were allowed to swim only on Wednesdays, the same night that the pool was drained and cleaned weekly. This policy insulted African American residents, who with the leadership of Dr. Griffin and the support of the Pasadena NAACP filed a lawsuit against the city. In 1942, the court ruled in favor of granting unrestricted access to the pool for everyone, regardless of skin color. This was a triumph in a time when segregation was the norm throughout most of the country, but it took five years and further action on the part of Dr. Griffin and the NAACP to get the pool reopened and fully desegregated in 1947.

Dr. Griffin died in 1992, after decades promoting people’s health and civil rights in Pasadena. You can actually see the location of her medical office at 891 N. Fair Oaks Avenue on the Walking Tour of the African American History of Pasadena.

Ruby McKnight Williams

Ruby McKnight Williams worked with Dr. Griffin and the NAACP Pasadena Chapter in the fight to open and desegregate Brookside Plunge. It was part of a lifetime of work she gave to the Pasadena NAACP in her 50 years as a member, where she also spent 16 combined years as president.

Born and raised in Topeka, Kansas, McKnight worked as a kindergarten teacher before coming to Pasadena around the same time that Edna Griffin arrived in the 1930s. She wanted to teach, but Pasadena did not hire Black teachers at that time (until George Garner). So she visited the professional women’s employment service. At first they offered her a position as a governess—after a talk with the manager, she was hired to take over the new colored women’s department of the Pasadena Employment Service. There she worked to help African Americans find employment in Pasadena, visiting businesses all over town to advocate for hiring African Americans. She was a fearless crusader for Pasadena’s African American community, often going to stores that didn’t have black employees or were mistreating them and talking to the owners.

McKnight married Melvin Williams in 1946. She joined the Pasadena NAACP and served as president from 1959 to 1960 and then served as president again from 1969 to 1982. Alongside Dr. Edna Griffin, she fought to make Brookside Plunge open to all people at all times. During her tenure as president of the NAACP Pasadena Chapter, she took up the cause of school and housing desegregation in Pasadena. During this period, the NAACP supported two national precedent-setting civil rights cases.

Ruby McKnight Williams was known as an outspoken and vocal activist for civil rights, a person who never minced words and spoke truth to power courageously. In 1958, the Pasadena NAACP honored her by naming an award after her, to be given to members who demonstrate excellence in community service.

Sources:

Anderson, C. (1995). Ethnic history research project, Pasadena, California. Design and Historic Preservation Office.

Colored singer proclaims his gratitude with song. (1933, February 12). Los Angeles Times, A5.

Ferron, S. (Transcriber). (1977). Interview with Benjamin F. McAdoo. Interviewed by Frances B. White. Pasadena Oral History Project, Pasadena Historical Society.

Fox, M. (2006, March 1). Octavia E. Butler, science fiction writer, dies at 58. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/01/books/octavia-e-butler-science-fiction-writer-dies-at-58.html

Harnisch, L. (2009, March 5). Rediscovering George Garner, March 5, 1939. The Daily Mirror. https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/thedailymirror/2009/03/rediscovering-g.html

Hubert, R., & Simon, C. (Eds.). (1985). A century of black Princes, 1883–1983. Hogan’s Typeworld.

McHale, M. (1987, April 7). Breaking the color barrier. Pasadena Star News, A1, A6.

Mosley, T., Kim, C., & Hagan, A. (2021, March 5). Octavia Butler’s Pasadena: The city that inspired her to create new worlds. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2021/03/05/octavia-butler-pasadena

Ramirez, B. (2021, March 15). Black history in Pasadena. A Noise Within. https://www.anoisewithin.org/black-history-in-pasadena/

Schertz Keller, L. (1990, December 6). Activist, 90, sees the fruits of her labor for equality. Los Angeles Times, 3.

Schiff, A. (2004, February 24). Tribute to Elbie J. Hickambottom, Sr. Vote Smart. https://justfacts.votesmart.org/public-statement/38695/tribute-to-elbie-j-hickambottom-sr

Smith, J.R. (1960, March 13). Fights for Negro rights. Independent Star-News, 9.

Stovall, M. (1963, July 27). Dr. Edna Griffin views problems with a physician’s practicality. Pasadena Star News, A3.

Stovall, M. (1966, May 7). Ruby Williams solves problems with right attitude, smile. Pasadena Star News, 3.

Teller of black historical tales dies. (1984, March 12). Pasadena Star News, A4.

The Octavia E. Butler Estate. (n.d.). About the author. Octavia E. Butler. https://www.octaviabutler.com/theauthor

Zorbas, E. (Ed.), & Delman, A. (Transcriber). (2006). Interview with Elbie J. Hickambottom. Interviewed by Sarah Cooper. Pasadena Heritage Oral History Project, Pasadena Heritage.